Article

Search Articles

Listen

Download Article Study Sheet

Grab the study sheet to review the highlights of this article.

Download SummaryRelated Articles

Get The Infographic

Get the full sized infopgraphic overview highlighting the key points discussed in this article.

Download Now

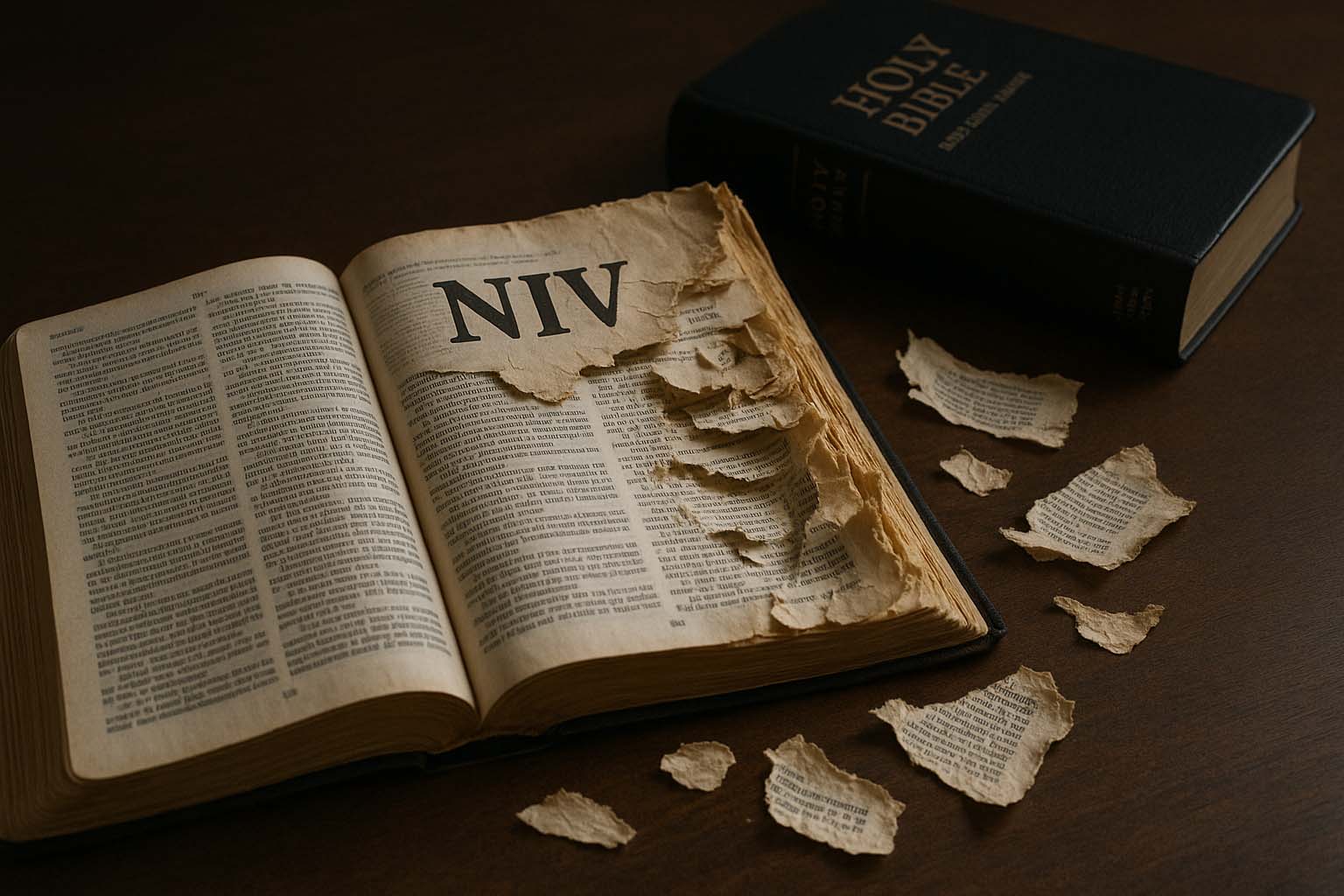

The NIV Bible Controversies: Translation Issues That Still Matter

Kenneth Long

Kenneth Long

Introduction: A Popular Bible with Lingering Questions

The New International Version (NIV) Bible has become one of the most widely used English translations of the Scriptures, praised for its readability and accessibility. However, beneath its popularity lies a deep and ongoing controversy surrounding its faithfulness to the original texts, its translation choices, and the theological implications of its revisions. These concerns are not merely academic; they touch on matters of doctrine, salvation, and trust in the written Word of God.

Manuscripts and the NIV: A Different Foundation

The roots of the controversy begin with the manuscript tradition on which the NIV is based. Unlike the King James Version (KJV), which relies on the Textus Receptus, the NIV is based on what scholars call the Critical Text—compiled from older, and in some cases fragmentary, manuscripts such as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus. Supporters of the Critical Text claim these are closer to the originals due to their antiquity, while critics argue that age does not necessarily equal purity, especially when such manuscripts were often isolated or corrected by scribes.

Omissions and Footnotes: Doctrinal Concerns

What alarms many believers is that certain verses included in the KJV are entirely omitted or bracketed in the NIV, accompanied by footnotes that question their authenticity. Verses such as Matthew 17:21, Acts 8:37, and Mark 16:9–20 are either relegated to footnotes or removed entirely. This raises concerns that critical doctrines— like Jesus’ deity, the virgin birth, or salvation through faith—could be minimized through these omissions.

A Case Study: 1 Timothy 3:16

One example often cited is 1 Timothy 3:16. In the KJV it reads, “God was manifest in the flesh,” a strong affirmation of the deity of Christ. In the NIV, the same verse reads, “He appeared in a body.” The change may appear subtle, but the implications are far-reaching. The former clearly identifies Jesus as God, while the latter is more ambiguous. Defenders of the NIV say this reflects older manuscripts; critics argue that it opens the door to doctrinal confusion.

Gender-Neutral Language: Faithful or Trendy?

Another area of concern is the NIV’s adoption of gender-neutral language, particularly in its 2011 revision. Words such as “man,” “father,” or “brothers” are often replaced with “people,” “parent,” or “brothers and sisters.” The translators maintain that this helps modern readers understand the inclusiveness of the original Greek. However, many see it as capitulating to modern cultural trends and obscuring the precision of the biblical text.

Dynamic Equivalence: Translating Thoughts, Not Words

Even beyond specific verses, the dynamic equivalence translation philosophy of the NIV itself is criticized. This method seeks to convey the “thought” or intent behind the original wording rather than translating word-for-word. While this can improve readability, it can also invite unintended bias. When translators interpret the meaning rather than preserve the words, theological nuance can be lost or skewed, especially in difficult or debated passages.

The Translation Committee: Diverse but Divided?

Supporters of the NIV argue that the translation committee was composed of scholars from a wide range of Christian backgrounds and denominations. However, critics counter that such a diverse committee may result in theological compromise, prioritizing broad acceptance over precision. There is no suggestion of conspiracy, but the concern is that subtle shifts in wording can have disproportionate impacts on doctrine.

Publishing and Profit: Business Behind the Bible

It's also worth noting that the NIV is a for-profit translation owned by Zondervan, a commercial publisher. While this does not inherently mean the translation is biased, it raises questions about motivations behind its updates. Regular revisions and copyright protections may prioritize market appeal over doctrinal consistency.

Accessibility vs. Accuracy: A Balancing Act

Despite these criticisms, it would be unfair to claim that the NIV is useless or untrustworthy in all respects. Its strength lies in its accessibility and readability, especially for new believers or casual readers. Its language is modern, its flow is natural, and for many, it has become their introduction to the Bible. But for in-depth study, apologetics, or defending core Christian doctrine, a more literal translation may be better suited.

Modernizing the Word: Clarification or Compromise?

The broader concern, ultimately, is not with the NIV alone but with a trend toward modernizing Scripture in ways that may dilute its power. Scripture is not a living document in the sense that it should evolve with culture; rather, it is the eternal Word of God, preserved through centuries by the Spirit of truth. When translation decisions are shaped more by readability or cultural sensitivity than by fidelity to the original, the line between clarification and compromise becomes thin.

Conclusion: Why It Still Matters

In conclusion, the controversies surrounding the NIV Bible are neither unfounded nor hysterical. They are the result of a careful examination of what is said—and what is not said—within the sacred text. Believers have every right to ask whether the version they hold in their hands reflects the original intent and message of the apostles and prophets. The answer may not lie in throwing out all modern translations, but in reading with discernment, comparing translations, and leaning on the guidance of the Spirit.

For those who prioritize doctrinal clarity, historical continuity, and the preservation of what the church has historically held as true, the NIV presents serious questions. It is not a question of accessibility, but of accuracy—and in that realm, the stakes are eternally high.

Tags: