Article

Search Articles

Listen

Download Article Study Sheet

Get the study sheet to review the highlights of this article.

Download SummaryRelated Articles

Get The Infographic

Get the full sized infopgraphic overview highlighting the key points discussed in this article.

Download Now

The Textus Receptus: Understanding the Legacy Behind the Modern Bibles We Read Today

Loading author...

Loading author...

The Road To Today

When we open the Bible, we often take for granted the long journey the text has taken to get to us.

Behind every verse we memorize and every sermon we hear lies a rich and sometimes complicated story

of transmission, translation, and preservation. One of the most important chapters in that story is

the Textus Receptus, a name that may sound unfamiliar to the average reader, but one that has

profoundly shaped how the Bible was read, understood, and trusted for centuries.

Let's explore what the Textus Receptus actually is, where it came from, why it's important, and how

it still impacts our understanding of God's Word today.

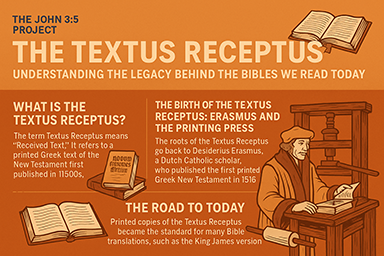

What Is the Textus Receptus?

The term Textus Receptus is Latin for “Received Text.” It refers to a printed Greek text of the

New Testament that was first published in the 1500s and became the textual foundation for many of the early Protestant Bible

translations, including the King James Version (KJV). Think of it as the official Greek manuscript collection

that Reformation-era translators relied on when bringing the New Testament into their own languages.

Unlike a single handwritten manuscript, the Textus Receptus was a compiled and edited version of several Greek

texts, printed and widely distributed during the era of the printing press. The name Textus Receptus itself

comes from a 1633 publisher's preface that claimed readers now had the text “received by all,” a phrase that

stuck and became the label for this edition.

The Birth of the Textus Receptus: Erasmus and the Printing Press

The roots of the Textus Receptus go back to Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch Catholic scholar

and humanist. In 1516, just before the Reformation exploded onto the scene, Erasmus

published the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament in Basel, Switzerland.

Erasmus didn't have access to the full range of ancient manuscripts that modern

scholars do today. In fact, he based his first edition on just a handful of late

Byzantine manuscripts, most of which came from the 12th century. Where he found

gaps—especially in the last few verses of Revelation—he sometimes back-translated

from the Latin Vulgate into Greek. In other words, when he didn't have a complete

Greek source, he used the Latin version to fill in the blanks.

Despite its flaws and rushed nature (the first edition was produced in only a few months),

Erasmus' Greek New Testament spread like wildfire. It was reprinted, revised, and eventually

improved by later editors like Robert Estienne (Stephanus) and Theodore Beza, both of whom

helped refine the work by comparing it with additional Greek manuscripts.

How the Textus Receptus Became the Standard

The key moment came in 1611 when the translators of the King James Version used the Textus Receptus

(specifically Beza's 1598 edition) as the basis for their English New Testament. This cemented the

TR's place in church history.

But it wasn't just the King James. Martin Luther used a similar Greek base when translating the

Bible into German. William Tyndale, the English reformer who translated the first English New

Testament from Greek, also worked from Erasmus's text. French, Dutch, Spanish, and other early

Bibles from the Reformation era all leaned on this same textual family.

Over time, this made the Textus Receptus not just a scholarly resource, but the default Greek

text of the New Testament for much of Protestant Europe. It became the backbone of doctrine,

preaching, memorization, and evangelism during the explosive growth of the Reformation.

Why the Textus Receptus Matters

To understand the impact of the Textus Receptus, we need to appreciate what it represented.

For the first time, the Bible was being translated into the common languages of Europe, and the

Greek source behind it was accessible, stable, and reproducible.

While the medieval church had long used the Latin Vulgate, a translation completed by

Jerome in the 4th century, the Reformation brought a desire to return to the original

languages—Hebrew for the Old Testament and Greek for the New. Erasmus's printed Greek

New Testament allowed that to happen. It gave translators a unified text that could be studied,

critiqued, and taught across national and linguistic borders.

More than that, many believers came to view the Textus Receptus as God's preserved Word,

handed down faithfully through the generations. It wasn't just a historical text—it was

treated as authoritative. Preachers and theologians trusted it, and countless believers

based their faith, hope, and salvation on verses translated from its words.

The Modern Debate: TR vs. the Critical Text

Fast forward to today, and things have changed quite a bit in the scholarly world. Modern Bible

translations like the NIV, ESV, NASB, and CSB are not based on the Textus Receptus. Instead,

they use what's known as the Critical Text—a Greek New Testament compiled using a much larger

and older collection of manuscripts, including some that date back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

In the 1800s, newly discovered manuscripts like Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus led

scholars to re-evaluate the Greek New Testament. These older manuscripts sometimes differed

from the TR in wording, order, or even entire verses. That raised questions: Was the TR

adding material that wasn't in the originals? Were these older texts more accurate?

As a result, the Nestle-Aland and United Bible Societies (UBS) editions of the Greek

New Testament were developed. These are what most Bible translators now use. Supporters

argue they reflect a more ancient and original form of the text.

But not everyone agrees.

Why Some Still Stand by the Textus Receptus

Many Christians—especially within the King James Only movement or traditional churches—still hold to

the Textus Receptus as the most trustworthy Greek text of the New Testament. Their reasons vary, but

common themes include:

- Providence: They believe God preserved His Word through the TR manuscripts.

- Continuity: The TR represents the textual tradition that was used and trusted by the church for centuries.

- Doctrinal Integrity: Some argue that the Critical Text omits or downplays verses that affirm the deity of

Christ, the authority of Scripture, or core doctrines of the faith.

- Stability: Unlike modern texts that undergo frequent revisions, the TR is seen as settled and unchanging.

So Which One Is Right?

The debate between the Textus Receptus and the Critical Text isn't going away anytime soon.

And to be fair, both sides make important points.

Supporters of the Critical Text are trying to reconstruct the earliest possible form of

the New Testament, based on the widest and oldest range of manuscripts. That's a noble goal.

Supporters of the Textus Receptus believe God didn't leave His Word in obscurity for

centuries, waiting to be rediscovered. They see the Reformation-era Bible as more

than historically significant—it's a part of God's providence in preserving truth.

At the end of the day, readers should understand what the Textus Receptus is, and how

it helped bring the Word of God into the hands of everyday people in their own languages.

Whether you read a Bible based on the TR (like the KJV or NKJV), or one based on the

Critical Text (like the ESV or NIV), it's vital to recognize the history behind the

pages you're reading.

A Text That Shaped the World

The Textus Receptus is more than a scholarly term—it's a symbol of a turning point in history.

In an age when access to Scripture was limited, the TR opened the floodgates. It was the

engine behind the Reformation Bibles. It helped define how millions came to know Christ,

preach the gospel, and defend the faith.

Even today, debates about translation and manuscript history often circle back to the Textus Receptus.

It may not be the default scholarly standard anymore, but its impact is still deeply felt in the church,

especially in how we view the authority, preservation, and trustworthiness of Scripture.

And for those who cherish the KJV or believe God's Word was preserved in the TR tradition,

this text remains not just received—but revered.

Tags: