Article

Search Articles

Listen

Download Article Study Sheet

Get the study sheet to review the highlights of this article.

Download SummaryRelated Articles

Get The Infographic

Get the full sized infopgraphic overview highlighting the key points discussed in this article.

Download Now

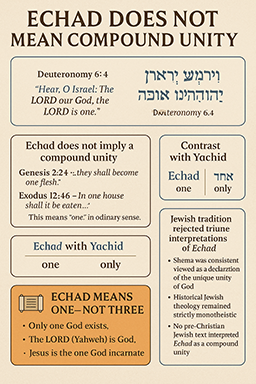

Does Echad Mean a Compound Unity? A Biblical and Linguistic Refutation

Loading author...

Loading author...

Introduction

A common Trinitarian argument hinges on the Hebrew word אֶחָד (echad), found in Deuteronomy 6:4:

"Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD." (KJV)

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל, יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְהוָה אֶחָד

Trinitarian apologists often assert that echad means a "compound unity" (i.e., one made up of multiple parts), and therefore, they claim, it leaves room for the concept of a triune God. But does the Hebrew word echad actually imply compound unity in the context of Deuteronomy 6:4 or anywhere else where God is described as echad?

The answer, based on sound Hebrew grammar and usage, is a resounding no. This article will demonstrate why this claim is linguistically dishonest, contextually invalid, and theologically misleading.

1. What Does Echad Mean in Hebrew?

The Hebrew word אֶחָד (echad) simply means "one" --- the number one, a singular unit, or a unified object. It is the cardinal number for "one" in Hebrew, just like "uno" in Spanish or "eins" in German.

Examples of echad as a simple "one":

Genesis 2:24 -- "...they shall become one flesh"

This is often used to claim "compound unity." However, it is a poetic way of saying unity in relationship, not a mixing of persons into one being. Two people remain distinct, but in covenant. It does not redefine "one" as "three."

Exodus 12:46 -- "In one house shall it be eaten..."

Echad describes a single house, not a compound of houses.

Genesis 42:11 -- "We are all one man's sons."

Refers to shared identity from one father; not that their father was multiple persons.

In each case, echad is being used in the plain sense of "one", and where there is any kind of plurality, that plurality is made clear from the context or surrounding words, not from the word echad itself.

2. Echad vs. Yachid: Is There a Distinction?

Some Trinitarians claim that if Moses wanted to convey an absolute oneness, he would have used the word "yachid" (יָחִיד) --- which means "only" or "solitary."

However, this argument falls apart for two reasons:

a. Yachid implies uniqueness or aloneness, not just numeric oneness.

- Yachid often implies isolation or even loneliness (e.g., Genesis 22:2 -- "your son, your only son").

- God is never described as yachid in the Old Testament, but that does not weaken His singularity. Rather, echad expresses the singularity of His being in the covenantal declaration of monotheism.

b. Echad is used precisely because it expresses numeric singularity in covenant.

Deuteronomy 6:4 is not trying to argue God is "unique" among other gods (which yachid might imply), but that YHWH is the only God Israel is to worship, with no division or multiplicity.

3. Hebrew Grammar: Echad Is a Cardinal Number, Not a Composite Label

In Hebrew grammar, echad functions exactly like the English word "one" --- it can modify singular nouns, and in certain contexts, it can refer to collective nouns (like "one cluster of grapes"), but this does not redefine the meaning of "one."

Common Misused Example: Genesis 1:5

"And the evening and the morning were the first day [yom echad]."

This does not mean the day is composed of parts; it means the first (or one) day in a series. Hebrew doesn't have a distinct word for "first" apart from the ordinal form, so echad can be used in that position. It still means one.

4. Deuteronomy 6:4 in Context: A Declaration of Monotheism

The Shema is the core monotheistic confession of Israel:

"YHWH our God, YHWH is one."

It does not say "YHWH is a compound unity." It says that there is only one God --- YHWH --- and He alone is to be worshipped.

Key points from the context:

- Deuteronomy 6 is a warning against idolatry (vv. 10--15). The emphasis is on exclusive loyalty to one God, not a hint of three-in-one beings.

- Ancient Israelite monotheism stood in stark contrast to Canaanite polytheism, which believed in divine families or councils of gods.

- If Moses were trying to hint at multiple persons in God, this would be the worst possible verse to do it --- as it would immediately confuse Israel's understanding of God's singularity.

5. Jewish Understanding: No "Compound Unity" Exists in Traditional Interpretation

For thousands of years, Jewish scholars --- fluent in biblical Hebrew --- never interpreted echad as implying multiplicity within God. This interpretation only arose much later as part of Christian apologetics defending the Trinity.

Ask yourself:

If echad implied a triune God, why did:

- No prophet,

- No scribe,

- No rabbi,

- No Jewish writer for 1500+ years

ever interpret it that way?

Because echad doesn't mean that.

6. The Real Reason the "Compound Unity" Argument Exists

The "compound unity" claim is an attempt to force a later doctrinal idea (the Trinity) back into a pre-Christian Hebrew word. It is eisegesis, not exegesis.

It misuses verses like:

- Genesis 2:24 (one flesh)

- Numbers 13:23 (one cluster of grapes)

In both cases, the plurality is explicit in the noun, not the word echad. Echad still simply means "one."

Conclusion: Echad Means What It Says --- One, Not Three

The Hebrew word echad does not support the Trinity. It does not mean a "compound unity" in and of itself. When plurality is meant in Hebrew, it is indicated elsewhere in the structure of the sentence or the surrounding words --- not by the word echad alone.

Deuteronomy 6:4 is the clearest affirmation of monotheism in the Bible --- not a coded hint of multiplicity.

The God of Israel is one God, not one divine "group."

And echad affirms that with linguistic clarity and theological force.

Further Reading

- Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew Lexicon: Echad -- "one" (not compound unity).

- Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament -- Echad is a numeral, nothing more.

- Rabbi Tovia Singer, Let's Get Biblical, vol. 1 -- discusses the misuse of echad by Trinitarians.

- Dr. Michael Heiser -- even he, while affirming plurality, notes echad alone does not support a compound unity.

Tags: